Charles Waldheim. Landscape as urbanism: a general theory. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2016.

In this general theory of landscape architecture Charles Waldheim mentions all the contemporary usual suspects: Rem Koolhaas and Bernard Tschumi (Parc de la Villette Competition), James Corner/Field Operations (Fresh Kills Landfill), Adriaan Geuze/West 8 (Eastern Scheldt Storm Surge Barrier), Chris Reed/Stoss (Lower Don Lands Competition), Eric Miralles and Carme Pinós (Igualada Cemetry), Alejandro Zaera-Polo and Farshid Moussavi (Yokohama Port Terminal and Barcelona Amphitheater), James Corner and Diller Scofidio + Renfro (High Line), West 8 and DTAH (Toronto Waterfront), Luis Callejas/Paisajes Emergentes (Caracas Airport Park), Kongjian Yu/Turenscape (Qunli Stormwater Park).

These landscape architects work in the shadow of infrastructural objects - the abattoir, the landfill, the rail track, the waterfront, the airport - and interweave natural ecologies with the social and cultural layers of the city. Landscape is examined "as the medium through which to conceive the renovation of the postindustrial city".

The author traces landscape in the West back to the crisis of Fordist economies and chooses Detroit as a canonical example (here he makes an interesting link to the Disabitato in Rome between the fourteenth and the nineteenth century). He also reconsiders Lafayette Park by Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig Hilberseimer and Alfred Caldwell and its effective use of landscape as the spacial and organizational media to construct urban order.

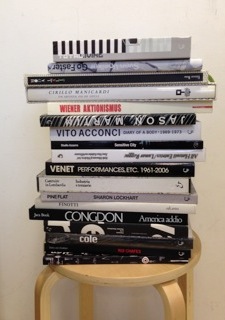

Waldheim also mentions all the right books: Ian McHarg's Design with Nature, James Corner's Taking measures across the american landscape and Recovering Landscape, Mohsen Mostafavi and Gareth Doherty's Ecological Urbanism, Denis Cosgrove's Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape, Charles Waldheim's The Landscape Urbanism Reader, W.J.T. Mitchell's Landcape and Power, Ludwig Hilberseimer's The New Regional Pattern, Dramstad, Olson and Forman's Landscape Ecology Principles in Landscape Architecture and Land-Use Planning.

After all this is a general theory so why does it feels like a BUT should follow? Maybe I was expecting that the final chapter would point at something new. Waldhein does recognize that the intellectual agenda of landscape urbanism is two decades old. He also asserts that the discourse on landscape urbanism, while hardly new in architectural circles, is rapidly being absorbed into the global discourse on cities.

For a general history of landscape architecture I also recommend ten lectures by Christophe Girot, Chair of Landscape Architecture at the ETH, Zurich.