Let me start by acknowledging the Italian architect Luigi Moretti and the seven issues of SPAZIO that he published between 1950 and 1953. He had something to say about Space and used his thoughts to structure a narrative. For those like me that have struggled for a while with the idea of practicing architecture and finally found themselves in the infinite stories that could be told about the discipline, his sophisticated writings will sound refreshing.

We find the clue for deciphering his first article right on the cover: a Doric façade (Vignola docet) on a cloudy background. Eclecticism and Unity of Language is a prize of those moments of clarity when various modes of expression - art, architecture, literature, music - come together in a consonant harmony and reach a dense maturity. The Golden Square of the Villa Adriana in Tivoli, San Pietro in Montorio by Bramante, La Rotonda by Palladio echo the happy times of Pericles, the early Renaissance, the extraordinary seventeenth century. But the plenitude of expression sooner or later wears out and gives way to eclecticism. These are the times when restless spirits start searching for the new essential relations that will constitute a new language. And who better than Carlo Mollino (the cloudy background comes from Casa Rivetti) to stand for the eclectics?

Perhaps it is from Mollino, whose obsession with women's waists and hips had so clearly influenced his practice, that Moretti took inspiration to write about the relations existing between the human body and the world of figurative arts. His article opened to Biagio Pace's text on the Discobolus and the issue of roman copies, which is still a very contemporary topic.

Moretti acknowledged the modern tendency to deviate from the human body and to progress toward exclusively formal relations, something that he traced back to the Roman Baroque where arms, hands and faces could be considered as signs placed to ensure a literal understanding of a hard and esoteric figurative language. He chose the

Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi by Bernini and one of the angels by Antonio Raggi for the Castel S. Angelo Bridge and made explicit their abstract formal qualities by zooming in on draperies, wings, clumps of greens, water and rocks.

[Images: Castel S. Angelo Bridge, Antonio Raggi; Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi, Bernini]

These complex structures don't allow for immediate perception, and are only readable sequentially. The composition is dissociated into tree or four compositional centres whose successive vision is determined by their relative positions in a determined space. Each fragment is a world in itself with its own gravitational forces. Moretti found that baroque plasticism and abstract languages shared the same formative process. He devoted a whole issue to abstract art and its relations to architecture.

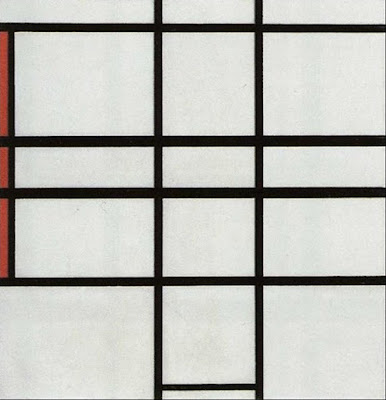

How did the ancients intended the relations between architecture and non-figurative pictorial spaces? The Romanesque walls striped in white and green or dark grey were the most abstract and concrete surfaces that Moretti knew about; he was dazzled by the simple law behind the process that led a wall structure, adding nothing, in the realm of the most violent and most pure pictorialism. By using materials of different colours and similar tectonic qualities, not only the resulting surface of the wall looked purely pictorial, but the very act of construction was enhanced. The Church of S. Francesco in Prato materialized Moretti's reading. He then identified a completely opposite strategy in the Baptistery of Florence, where only bearing structures are striped while wall surfaces with no tectonic strength are characterized by lines, squares, and circles, all abstract figures that naturally suggest a connection to the abstract works of Piet Mondrian.

[Images: Church of S. Francesco, Prato; Baptistery, Florence]

[Image: Composition with red, Piet Mondrian, 1936]

In Discontinuity of Space in Caravaggio Moretti wrote about the instrumental use of light in Baroque paintings: where there is light there is also a body, a fact; while the dark is emptiness, a sidereal and eternal void. Caravaggio's inspiration may have been the atmospheres of Rome during the summer. The blazing sun draws the deepest shadows on palaces and churches: certain elements almost disappear in the background, others glow in the light as if they were apparitions. But then of course Moretti was an architect and was interested in reading reality in a tectonic way. In seventeenth century Roman architecture, light was a synonym of strength and was used to emphasize those architectural elements where the loads are condensed. The architectural counterpart of Caravaggio is Borromini: on the church of S. Carlino alle Quattro Fontane, the midday light points to the structural role of the four columns. Light is a construction material.

In The Value of Moldings, Moretti wrote: "Ancient architects realized through sensibility and cultivated experience that a wall is in itself a worn-out reality, untouched and bear. To make it come alive and be expressive - dense with existence - one must change it, evoking forces, making it erupt with movement and corrugations to exalt its presence. [...] Cornices condense the sense of existence because they impose themselves on our vision with their neat, rapid, cutting sequences of distinctive frequencies and differences. Their spaces are vivid and dense with signs, and they engage our attention to the utmost. [...] Everything that is visible communicates with us through its surface."

The architectural surface insists on interior spaces which consequently have specific geometry, determined dimension and density, and are charged with certain energy according to the pressure that the liminal masses of the construction exert on them.

This charged void and the way that it can be structured into sequences is essentially what Moretti was interested in.

[Image: Diagram of the structural sequence of S. Pietro in Vaticano]

Spaces speak quite loudly to our bodies: we cannot help but feel on our skin the pressure of a doorway, the limited liberation of an atrium, the opposition of a wall, the brief pressure of a gap, the sense of liberation of a nave and contemplation of a dome. Our reactions are immediate and instinctive but our bodies can also get used to almost anything. And that's why architects have such a big responsibility.

We spend most of our lives in interior spaces that powerfully affect our physical and mental well-being. We should always wonder: are we turning up like the boiling frog?