The magazine Stile Industria was founded in 1954 by Alberto Rosselli on the conviction that architects and designers should be concerned with the form of all things industrial. It was the only Italian magazine dedicated solely to industrial design and it run for forty-one issue, almost ten year. At the time when Domus (Gio Ponti) was still publishing objects that were crafted by artisans in small numbers, Rosselli chose to discuss only mass production.

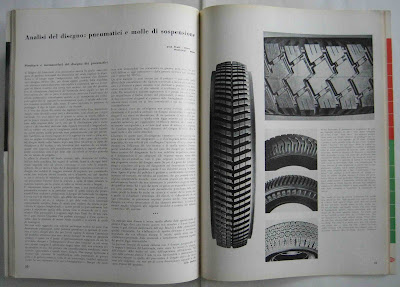

Next to chairs, tables, and kitchenware he presented toilets, cars, measuring instruments, and truck tires. He invited people like Max Bill, Gillo Dorfles, Angelo Tito Anselmi, Angelo Mangiarotti and Ettore Sottsass to write about how industries could condense beauty and function into objects capable of changing the way we live our everyday lives. He pushed to establish organizations like the ADI (Italian Association for Industrial Design), and was on the selection committee of the Compasso d'oro.

Stile industria introduced to the italian public the work done at the Institute of Design in Chicago, at the Hochschule für

Gestaltung in Ulm, and at the Royal College of Art in London. Rosselli reported back from Aspen between 1956 and 1959, from the 1958 Work Exhibition in Brussels, and 1960 World Design Conference in Tokyo.

Nothing was too big or too small: prefabricated elements were given the same space as precision objects, graphic design and packaging. All content was carefully dissected on the double page so that the reader could grasp every detail. Thanks to Rosselli and Stile Industria we learned to look closer and differently to ten years of industrial production.

Albe Steiner, Bruno Munari, Pino Tovaglia, Giovanni Pintori, and Michele Provinciali among others designed the beautiful covers that for a decade promoted a cultural take on industrial objects. And even though it is a selection of a larger production, it is a significant one.

Many of the industries presented on Stile Industria did not preserve complete records of their work. Designers and architects sometimes kept the drawings and we can use their archives to piece together a fragmented overview of the industry. The magazine is a useful sample, a condenser of the many cultural inputs that surrounded this ten years of bustling production.

The magazine was too consistently sophisticated to be turned into a medium for selling publicity. According to the revealing text on Rosselli by Giovanni Klaus Koenig this was the main reason for the publisher to shut it down after ten year of loyal service.